Mechanics of Living

How Phonograph Records Are Made

PSM Picture Story

by Robert F. Smith and Harry Samuels

The silent black disc that makes noises when needled is chiefly shellac, lamp-black and limestone. In its manufacture, however, pure gold, wax, glass, copper, nickel and sometimes chromium are used by the craftsmen who operate the intricate and delicate machines that squeeze sound into a scratch.From beginning to end, the commercial manufacture of records is a tremendously exacting process. For example, 50 percent of the wax-coated glass discs on which the music is recorded are rejected before reaching the cutting room. The accompanying pictures tell the story.

- Liquid wax is poured on a pre-heated glass plate, the first step in making a master disk. The plate is then cooked until the wax forms a layer .028-inch thick. Then the wax is hardened.

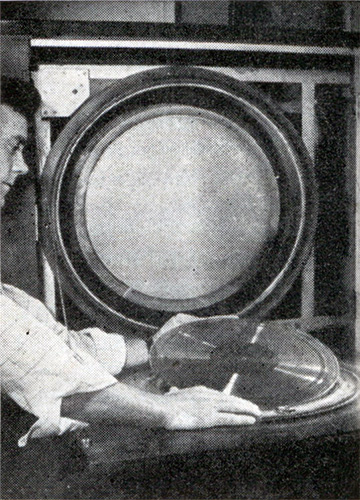

- Here music is recorded on the wax disk. Sounds picked up by the amplifier create electrical impulses that vibrate a sapphire stylus. The stylus cuts spiral grooves with wavy sidewalls. Cutting is watched through a microscope.

- Cut with 88 to 136 grooves to the radial inch, depending on the length of the recording, the wax is put in a vacuum chamber to be “sputtered” with an extremely thin coat of 24-karat gold.

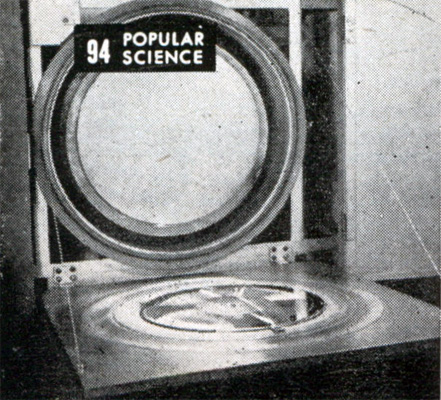

- Center of vertical disk in background is a gold sheet (cathode) from which the wax disk, resting on a plate (anode), gets its gold finish via an 1,800-volt charge.

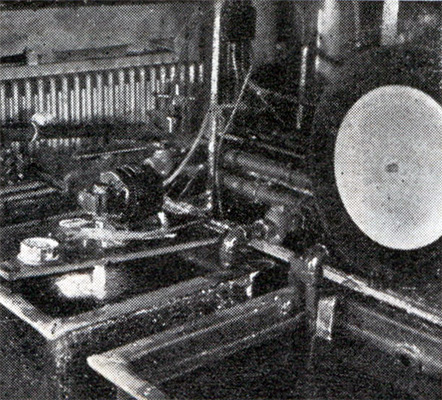

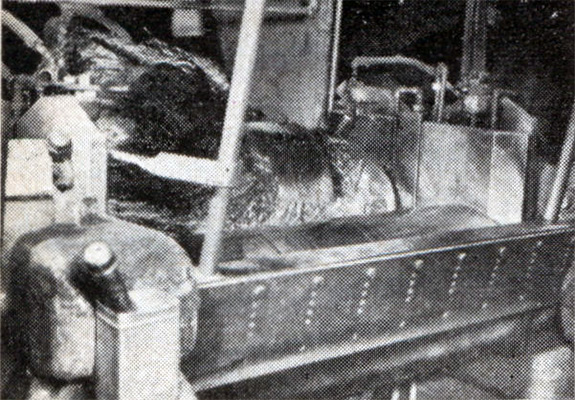

- Another metal plating applies a crust of copper .035-inch thick to the gold-coated wax. At left, a motor spins a disk as it is plated. At right, a disk rests on a hinged board after plating.

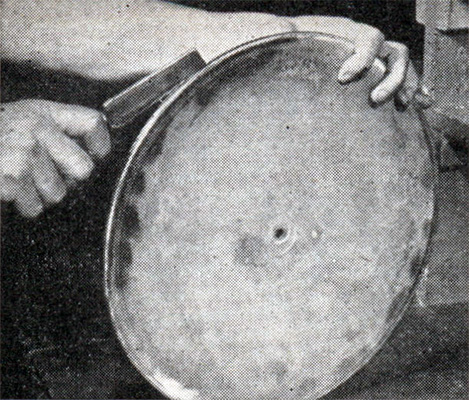

- Plate is split and glass-wax core is broken from the gold-faced copper plate that now becomes the № 1 master. Master has ridges where wax disc had grooves.

- Here № 1 mold, made from № 1 master, has just emerged from a bath in which it acquired a thin plate of nickel to harden its face. A similar coat of copper completes the mold. Master and mold are still attached.

- A separating tool detaches master from mold. № 1 mold’s face is an exact duplicate of the original recording. By subsequent plating and separating operations, № 2 master is made from № 1 mold and the final mold, № 2, from № 2 master.

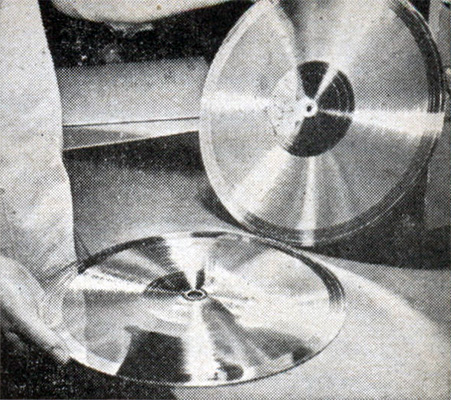

- Separation is now complete and № 1 mold is ready to be used to fashion № 2 master. The stamper, which presses the final product—the commercial record—is made from № 2 mold.

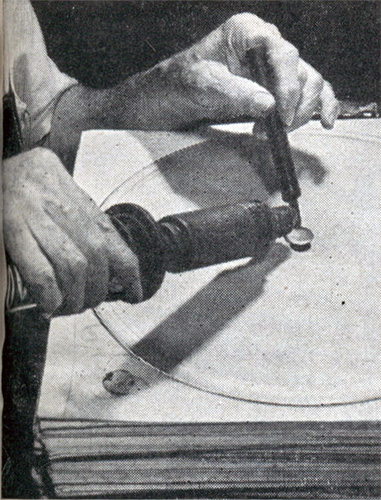

- The mold has an imperfect center hole. Here a craftsman solders a plug to the back of the nickel-faced copper mold in the first step toward putting a new hole in the exact center of the mold. This is a delicate operation.

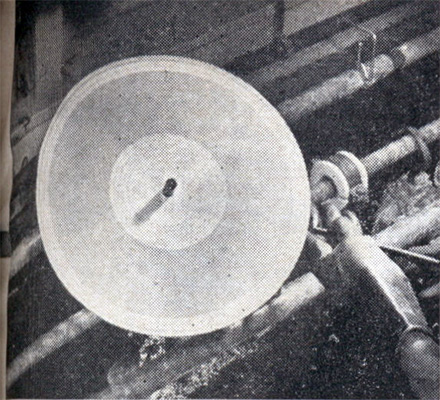

- Through a microscope mounted on a centering machine, the operator can adjust the placing of the disk so that its grooves run true around the center of the supporting plate. In the operator’s left hand is a lever that he pulls to punch the hole when disk is centered.

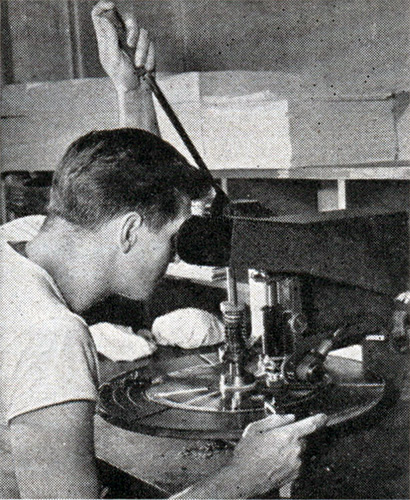

- The mold can be played. Here an expert listens to one in the RCA-Victor department where original masters are made. A defect in a recording is marked at its exact spot on the mold.

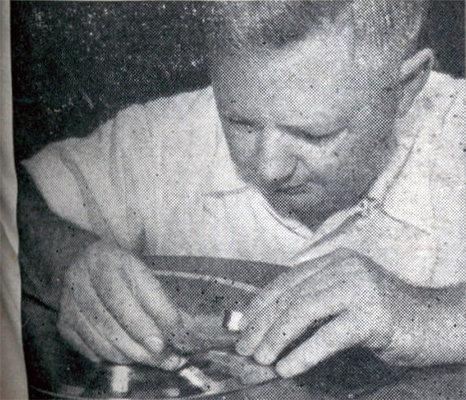

- A rehabilitation expert (below) removes a clicking sound from a mold.

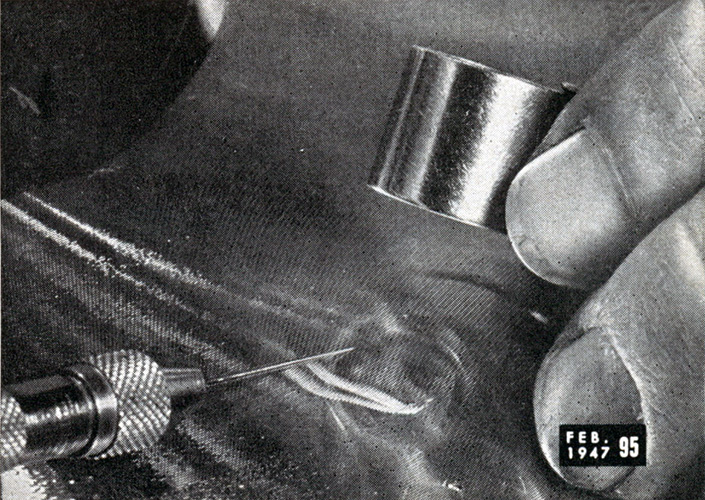

At rightBelow that is a close-up of a retouching job. The needle point of the tool actually fits in the groove and enables the craftsman to remove bumps and nicks. One expert spent six months restoring a Caruso master on which a worker had dropped a hammer.

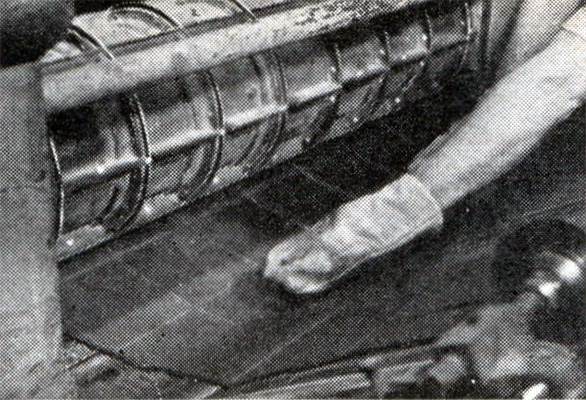

- Production of phonograph records starts with the mixing of a compound—shellac, lamp-black and limestone—from which records are made. Here a machine rolls the mixture into a long blanket.

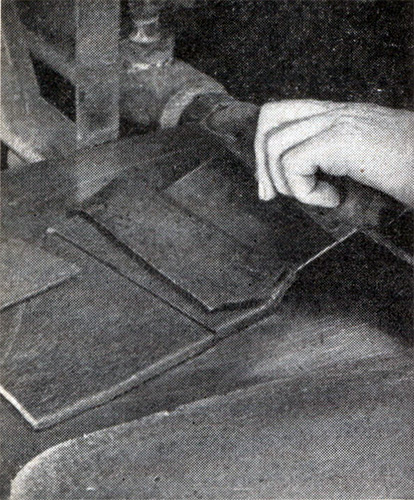

- As the blanket of compound travels on the machine’s belt it is cut into six-inch squares by the knife edges on the roller. After they have been cut, the squares continue on the belt and pass under blowers to be cooled and dried until they are in a brittle condition.

- At the end of their journey, the squares are stacked for future use in the record-pressing room. Lampblack is added to the compound out of which the squares are made only to give the finished record its color.

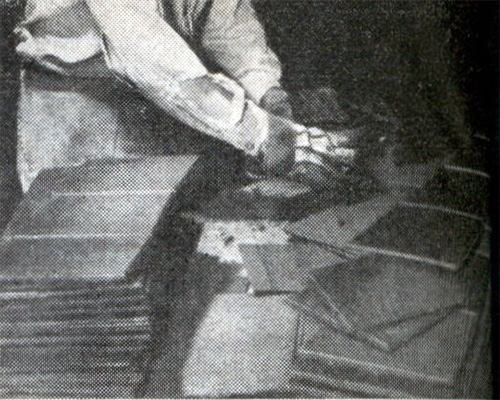

- In the pressing room enough squares to make a record are placed on a steam table and heated until they are pliant. Pressing-machine operator folds the square to make a “biscuit” as the trade calls the presser compound.

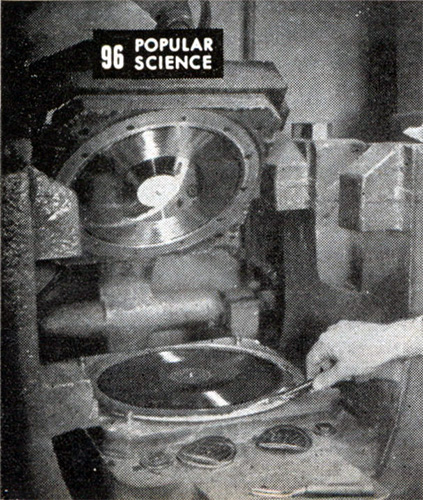

- This is a pressing machine about to make a record. In the top section is the stamper for the B side of the record. Its label is on the spindle in the center. In the bottom section is the A-side stamper, its label barely visible under the biscuit. In foreground are labels and the tool used to lift the record.

- Here a record is made in the presser, a machine resembling a waffle iron. Pressing is done automatically. Steam at 310 degrees F. heats the stampers, and the compound is forced into the impressions on the stampers by pressure of 1,800 pounds.

- The press is opened and a record, now nearly finished, is removed. The label for the next B side is already in position. Skilled operators turn out a record about every 48 seconds.

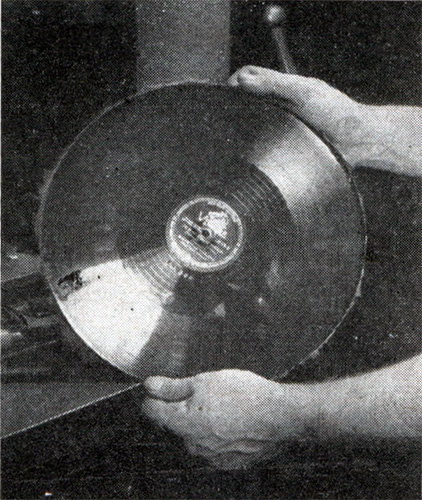

- The record comes out of the pressing machine with rough edges, but except for that it is ready for music stores throughout the nation. RCA-Victor is continually experimenting with new materials for making records.

- The record is held by two felt-covered plates and rotated. A girl holds a piece of emery cloth against its rim to smooth its edges. Next it is slipped into an envelope, ready for market.

Quoted from the February 1947 issue of Popular Science.

— MordEth

![[The Talking Machine Forum - For All Antique Phonographs & Recordings]](/styles/we_universal/theme/images/the_talking_machine_forum.png)